The optimization of nonradiative recombination losses through interface engineering is key to the development of efficient, stable, and hysteresis-free perovskite solar cells (PSCs). *

In the article “Interfacial Engineering with One-Dimensional Lepidocrocite TiO2-Based Nanofilaments for High-Performance Perovskite Solar Cells” Shrabani Panigrahi, Hussein O. Badr, Jonas Deuermeier, Santanu Jana, Elvira Fortunato, Rodrigo Martins and Michel W. Barsoum, for the first time in solar cell technology, present a novel approach to interface modification by employing one-dimensional lepidocrocite (henceforth referred to as 1DL) TiO2-based nanofilaments, NFs, between the mesoporous TiO2 (mp TiO2) and halide perovskite film in PSCs to improve both the efficiency and stability of the devices. *

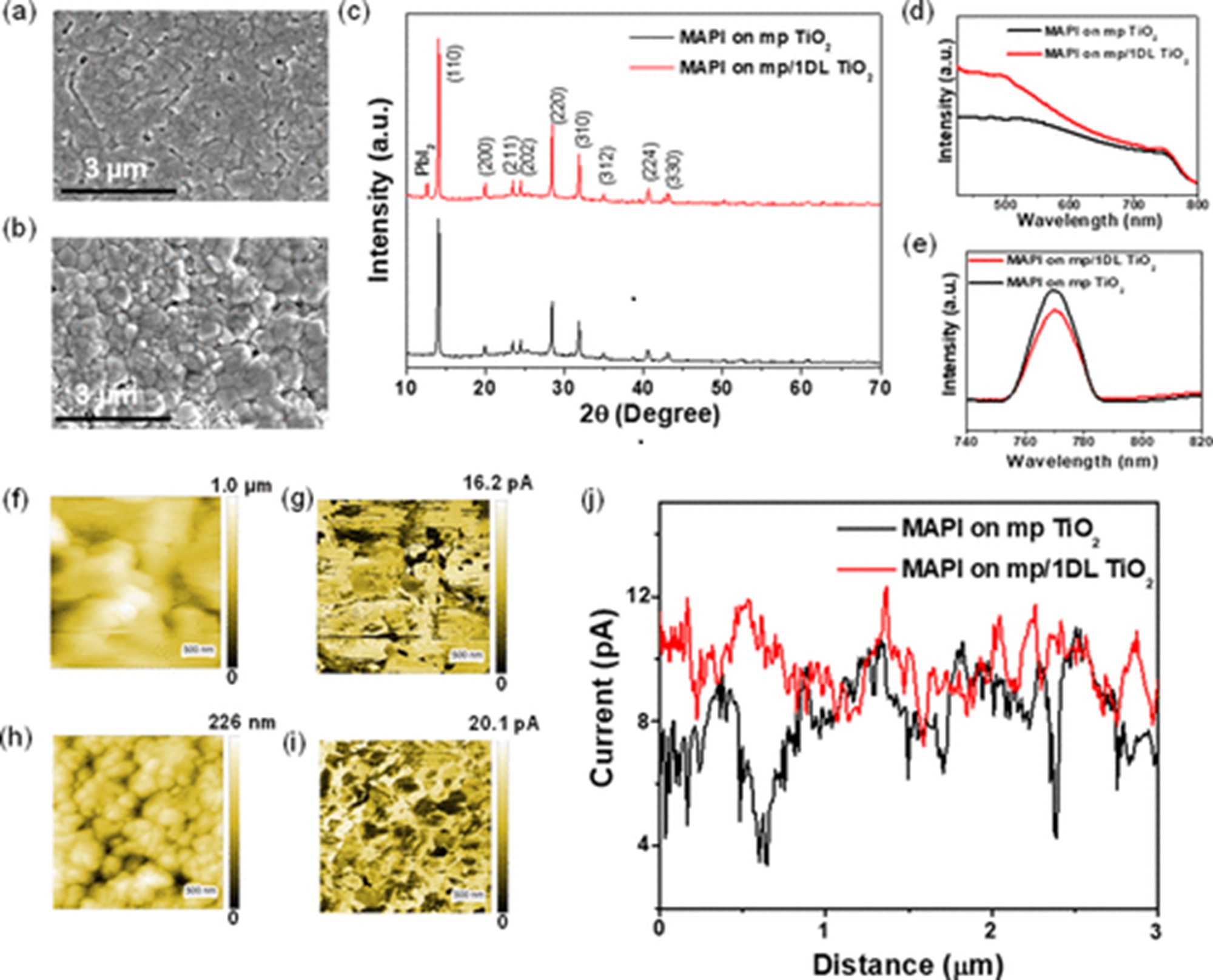

The 1DLs can be easily produced on the kilogram scale starting with cheap and earth-abundant precursor powders, such as TiC, TiN, TiB2, etc., and a common organic base like tetramethylammonium hydroxide. Notably, the 1DL deposition influenced perovskite grain development, resulting in a larger grain size and a more compact perovskite layer. Additionally, it minimized trap centers in the material and reduced charge recombination processes, as confirmed by the photoluminescence analysis. *

The overall promotion led to an improved power conversion efficiency (PCE) from 13 ± 3.2 to 16 ± 1.8% after interface modification. The champion PCE for the 1DL-containing devices is 17.82%, which is higher than that of 16.17% for the control devices. *

The passivation effect is further demonstrated by evaluating the stability of PSCs under ambient conditions, wherein the 1DL-containing PSCs maintain ∼87% of their initial efficiency after 120 days. *

The article not only presents cost-effective, novel, and promising materials for cathode interface engineering but also an effective approach to achieve high-efficiency PSCs with long-term stability devoid of encapsulation. *

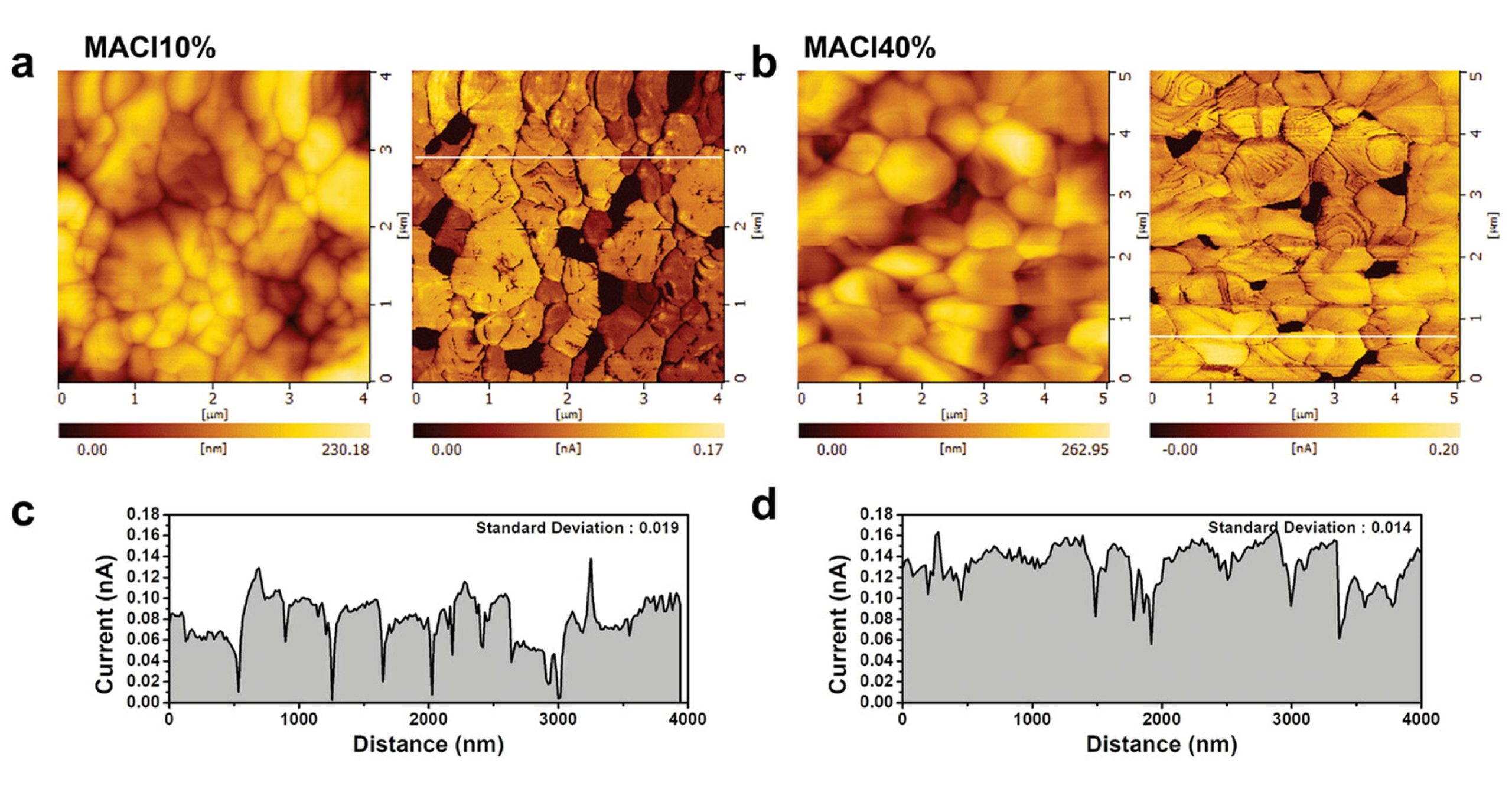

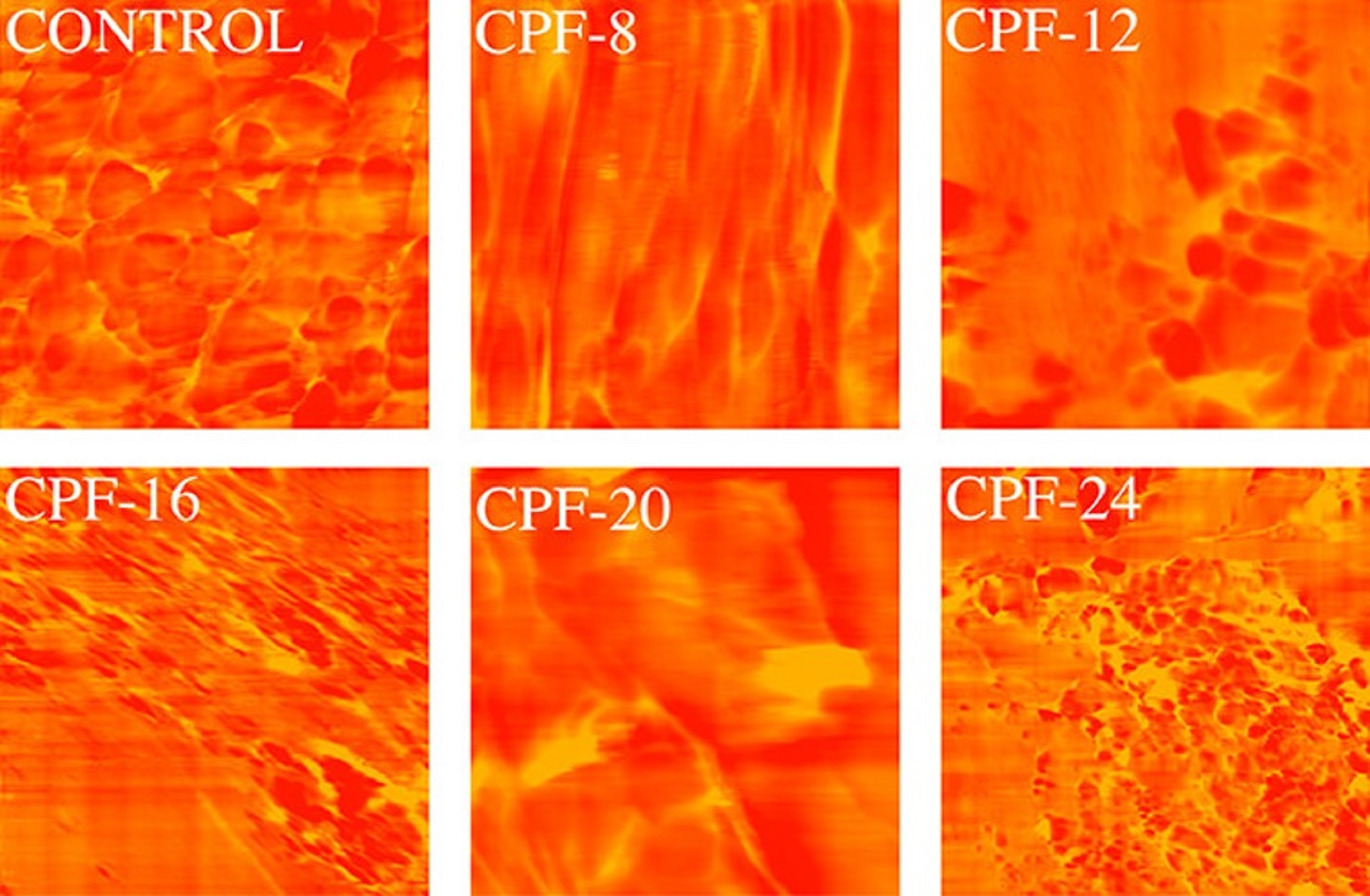

To get a deeper understanding of the enhanced photocurrent production within the perovskite layer, the authors used photoconductive atomic force microscopy (pcAFM) to map the photocurrent distribution at the nanoscale for the same perovskite layers on both types of ETLs. *

pcAFM measurements were taken in air with a commercially available Atomic Force Microscopy by using conductive PtIr-coated NanoWorld Pointprobe® CONTPt silicon AFM probes (typical resonance frequency = 13 kHz, typical spring constant = 0.2 N/m) and a current detector holder. A light source was used to light the samples. *

Characterization of the perovskite films (MAPbI3 is denoted as MAPI inside figure) deposited on mp TiO2 and mp/1DL ETLs: (a, b) FESEM micrographs, (c) XRD patterns, (d) UV/vis absorption, and (e) PL spectra. (f, h) AFM topography images and (g, i) corresponding pcAFM photocurrent images of the perovskite layers deposited on mp TiO2 and mp/1DL TiO2 ETLS, respectively. (j) Photocurrent line profiles across the perovskite layers.

*Shrabani Panigrahi, Hussein O. Badr, Jonas Deuermeier, Santanu Jana, Elvira Fortunato, Rodrigo Martins and Michel W. Barsoum

Interfacial Engineering with One-Dimensional Lepidocrocite TiO2-Based Nanofilaments for High-Performance Perovskite Solar Cells

ACS Omega 2024, 9, 51, 50820–50829

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c09516

Open Access The article “Interfacial Engineering with One-Dimensional Lepidocrocite TiO2-Based Nanofilaments for High-Performance Perovskite Solar Cells” by Shrabani Panigrahi, Hussein O. Badr, Jonas Deuermeier, Santanu Jana, Elvira Fortunato, Rodrigo Martins and Michel W. Barsoum is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third-party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.