Collagen is the most abundant structural protein in mammals. *

Type I collagen in its fibril form has a characteristic pattern structure that alternates two regions called gap and overlap. The structure and properties of collagens are highly dependent on the water and mineral content of the environment. *

In the article “Interfacial water on collagen nanoribbons by 3D AFM” Diana M. Arvelo, Clara Garcia-Sacristan, Enrique Chacón, Pedro Tarazona and Ricardo Garcia describe how they apply three dimensional atomic force microscopy (3D AFM) to characterize at angstrom-scale resolution the interfacial water structure of collagen nanoribbons.*

Three-dimensional AFM (3D AFM) is an AFM method developed for imaging at high-spatial resolution solid–liquid interfaces in the three spatial coordinates.*

This method has provided atomic-scale images of hydration and solvation layers on a variety of rigid and atomically flat surfaces, such as mica, gibbsite, boehmite, graphite, or 2D materials.*

However, imaging hydration layers on soft materials such as collagen is more challenging than on atomically flat crystalline surfaces.*

On the one hand, the force applied by the AFM tip might deform the protein. On the other hand, the height variations across gap and overlap regions might complicate the imaging of interfacial water.*

In recent years, 3D AFM has expanded its capabilities to image interfacial water on soft materials such as proteins, biopolymers, DNA, lipids, membrane proteins, and cells.*

Those experiments were performed with hydrophilic SiOx AFM tips which are negatively charged under neutral pH conditions.*

The imaging contrast mechanisms and the role of the AFM tip’s composition on the observed solvation structure are under discussion.*

More generally, both theory and experiments performed with very high salt concentrations indicated that the contrast observed in 3D AFM reflects an interplay between water particle and surface charge density distributions.*

For their article the authors apply 3D AFM to study at molecular-scale spatial resolution the structure of interfacial water on collagen nanoribbons.*

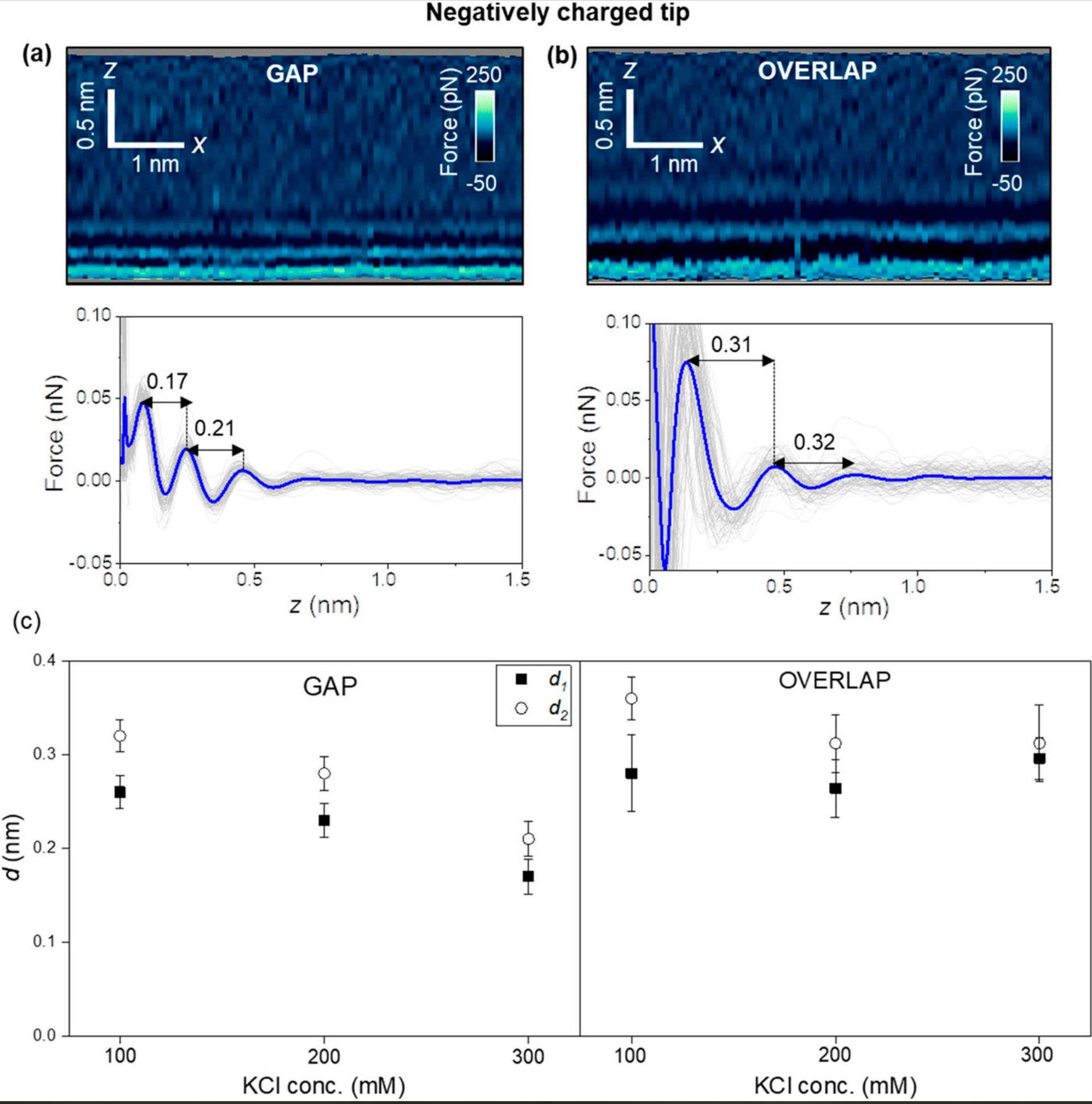

Diana M. Arvelo et al. study the influence of the AFM tip’s charge and the salt concentration on the interfacial solvent structure. They report that the interfacial structure depends on the water particle and ion charge density distributions. A non-charged AFM tip reveals the formation of hydration layers on both gap and overlap regions. A negatively charged AFM tip shows that on a gap region, the solvation structure might depart from that of the hydration layers. This effect is attributed to the adsorption of ions from the solution. Those ions occupy the voids existing between collagen molecules in the gap region. *

A home-made three-dimensional AFM was implemented on a commercially available AFM. 3D AFM was performed in the amplitude modulation mode by exciting the AFM cantilever at its first eigenmode.

At the same time when the AFM cantilever oscillates with respect to its equilibrium position, a sinusoidal signal is applied to the z-piezo to modify the relative z-distance between the sample and the AFM tip. *

Diana M. Arvelo et al. have used z-piezo displacements with amplitudes of 2.0 nm and a period (frequency) of 10 ms (100 Hz). The z-piezo signal is synchronized with the xy-displacements in such a way that for each xy-position on the surface of the material, the AFM tip performs a single and complete z-cycle. The z-data are read out every 10.24 µs and stored in 512 pixels (256 pixels per half cycle). Each xy-plane of the 3D map contains 80 × 64 pixels. Hence, the total time to acquire such a 3D-AFM image is 52 s.*

The 3D AFM experiments were performed with two types of AFM probes with different surface chemistries which have different chemical properties in aqueous solutions.*

The high-density carbon/diamond-like AFM tips grown on quartz-like AFM cantilevers that Diana M. Arvelo et al. et al used ( NanoWorld Ultra-Short Cantilevers USC-F1.2-k7.3 for high-speed AFM) remain uncharged at pH 7.4 and are called “neutral” AFM tips in the article.

The silicon AFM cantilevers with silicon AFM tips (NanoWorld Arrow-UHFAuD ultra-high frequency AFM probes) are negatively charged at neutral pH (silicon tips for short in the text) and were used to observe the formation of collagen nanoribbons.

All silicon AFM tips are readily oxidized and are usually covered by a thin native oxide layer which is hydrophilic.

The hydroxyl groups on the surface of the silicon AFM tip become negatively charged while the carbon AFM tips remain neutral (unchanged).

To image at angstrom-scale resolution, the interfacial water structure on the collagen requires reducing the lateral and vertical imaging sizes, respectively, to 5 and 1.5 nm.*

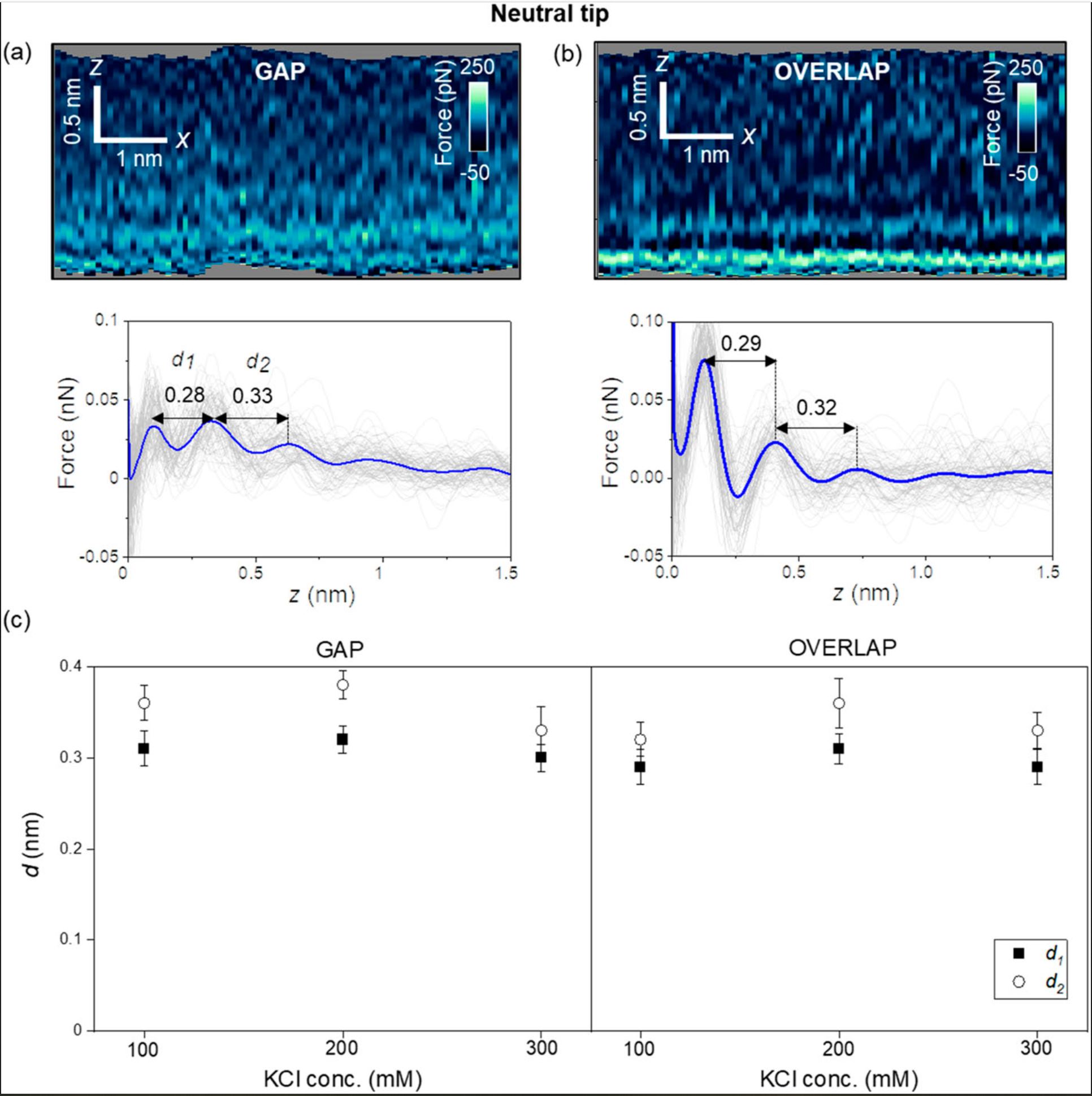

First, the authors introduce the results obtained with carbon-based tips (uncharged, NanoWorld Ultra-Short Cantilevers USC-F1.2-k7.3 for high-speed AFM). Figure 2 (of the cited article) shows some representative 2D force xz panels obtained on gap and overlap regions of a collagen nanoribbon in a concentration of 300 mM KCl. The panels are extracted from a 3D AFM image. The interlayer distances in a gap region are d1 = 0.28 nm and d2 = 0.33 nm (average values) [Fig. 2(a)], while those in an overlap region are d1 = 0.29 and d2 = 0.32 nm (average values) [Fig. 2(b)]. Those values coincide within the experimental error with the values expected for hydration layers on hydrophilic surfaces.

Next, the authors repeated the experiment using other salt concentrations. Figure 2(c) shows that the interlayers distances (within the experimental error) do not depend on the salt concentration or the collagen region. Diana M. Arvelo et al. remark that entropic effects make the second layer more disordered than the first; therefore, d2 ≥ d1.

The structure and properties of collagens are highly dependent on the water and mineral content of the environment.

For a neutral AFM tip (USC-F1.2-k7.3), the interfacial water structure is characterized by the oscillation of the water particle density distribution with a value of 0.3 nm (hydration layers). The interfacial structure does not depend on the collagen region.

For a negatively charged AFM tip (NanoWorld Arrow-UHFAuD ultra-high frequency AFM probes) the interfacial structure might depend on the collagen region.

Hydration layers are observed in overlap regions, while in gap regions, the interfacial solvent structure is dominated by electrostatic interactions. These interactions generate interlayer distances of 0.2 nm.

The achieved results still need to be explained by the theory of 3D AFM. More detailed theoretical simulations, which are beyond the scope of the cited study, will be required to quantitatively explain the interlayer distances observed over gap regions.

However, the results presented by the authors highlight the potential of 3D AFM to identify the solvent structures on proteins and the complexity of those interfaces.*

Interfacial liquid water structure on collagen provided by an uncharged tip. (a) 2D force maps (x, y) of the interfacial water structure in the gap region. The map is obtained in a 300 mM KCl solution. The force–distance curves in the bottom of the image are obtained from the top panel. (b) 2D force maps (x, y) of the interfacial water structure in the overlap region. The force–distance curves in the bottom of the image are obtained from the top panel. (c) Statistics of d1 and d2 distances measured from several collagen–water interfaces. The individual force–distance curves from the bottom panels of (a) and (b) are plotted in gray. The average force–distance curve is highlighted by a thick continuous line. The experiments are performed with USC-F1.2-k7.3 cantilevers. Experimental parameters: f = 745 kHz; k = 6.7 N m−1; Q = 8.3; A0 = 150 pm; Asp = 100 pm.

Interfacial liquid water structure on collagen provided by a negatively charged tip. (a) 2D force maps (x, y) of the interfacial water structure in the gap region. The map is obtained in a 300 mM KCl solution. The force–distance curves in the bottom of the image are obtained from the top panel. (b) 2D force maps (x, y) of the interfacial water structure in the overlap region. The force–distance curves in the bottom of the image are obtained from the top panel. (c) Statistics of d1 and d2 distances measured from several collagen–water interfaces. In the bottom panels of (a) and (b), the individual force–distance curves from the bottom panels of (a) and (b) are plotted in gray. The average force–distance curve is highlighted by a thick continuous line. The images were captured using ArrowUHF AuD cantilevers. Experimental parameters: f = 745 kHz; k = 8.3 N m−1; Q = 4.5; A0 = 170 pm; Asp = 100 pm.

*Diana M. Arvelo, Clara Garcia-Sacristan, Enrique Chacón, Pedro Tarazona and Ricardo Garcia

Interfacial water on collagen nanoribbons by 3D AFM

Journal of Chemical Physics 160, 164714 (2024)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0205611

The article “Interfacial water on collagen nanoribbons by 3D AFM” by Diana M. Arvelo, Clara Garcia-Sacristan, Enrique Chacón, Pedro Tarazona and Ricardo Garcia is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third-party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.