Matsuo et al., recently published a landmark study in Nature Communications (vol. 14, article 79, Jan 10 2023). , looking at how cells recognize and resolve ribosome collisions—a critical event in obeying translational fidelity and avoiding protein quality control failure.

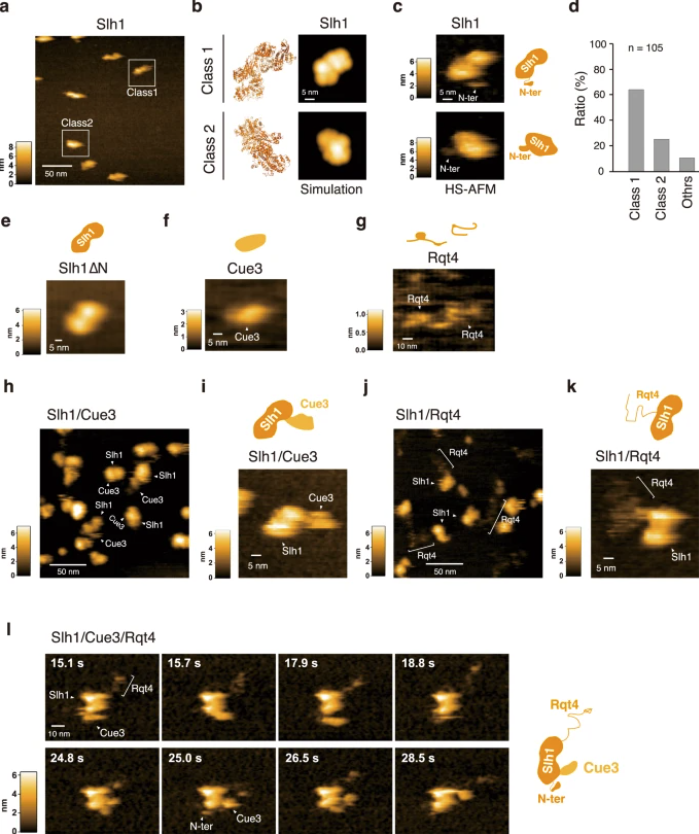

The researchers employed a combination of molecular genetics, biochemical assays, ubiquitin-binding studies, and advanced imaging. Key steps included mutational deletion of ubiquitin‐binding domains in RQT subunits, affinity assays for K63-linked ubiquitin chains, and highspeed atomic force microscopy (HSAFM) to visualize complex behavior at the molecular level. Notably, they used intrinsically disordered regions of Rqt4 mapped by realtime HSAFM.

The study shows that Cue3 and Rqt4 of the RQT complex interact with the K63-linked ubiquitin chain and facilitate the recruitment of the RQT (ribosome-associated quality control trigger) complex to ubiquitinated colliding ribosomes. Deletion of either domain abolished RQT’s ability to dissociate colliding ribosomes. Crucially, HSAFM revealed that Rqt4’s flexible disordered segments expand the interaction radius, enabling effective engagement with the ubiquitin chain. This expanded search capability enhances timely RQT recruitment and ribosome splitting before rogue collisions build up.

These findings elucidate a molecular “decoding” mechanism—how RQT interprets the ubiquitin code (specifically K63 ubiquitination) and transforms it into mechanical action, splitting ribosomal subunits to facilitate quality control. This work provides a mechanistic link between ubiquitin signaling and translational rescue pathways in the cell NanoWorld’s USC-F1.2-k0.15, designed for resonance frequencies of 1.2 MHz and tip radii below 10 nm, were used in the high-speed AFM studies that were crucial to this investigation.

Matsuo, Y., Uchihashi, T. & Inada, T. Decoding of the ubiquitin code for clearance of colliding ribosomes by the RQT complex. Nat Commun 14, 79 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35608-4

Decoding the Ubiquitin Code: How the RQT Complex Clears Colliding Ribosomes

a HS-AFM image of Slh1. Two major particles were indicated as Class1 and Class2. b The pseudo-AFM images of Slh1 belonging to Class1 and Class2 particles, which were simulated using predicted Slh1 structure lacking N-terminal region by Alphafold2. c The HS-AFM images and schematized molecular features of Slh1. d Classification of Slh1 particles. All particles used for the classification were presented in the supplementary Fig. 4. e HS-AFM images of Slh1 lacking N-terminal region (Slh1∆N). f HS-AFM image of Cue3. g HS-AFM image of Rqt4. h, i HS-AFM images of Slh1/Cue3 complex. j, k HS-AFM images of Slh1/Rqt4 complex. l The time-lapse HS-AFM images of the RQT complex. All experiments were performed at least twice with highly reproducible results.

This article beautifully merges state-of-the-art structural biology with nanotechnology tools to reveal how molecular collisions are detected and resolved. The incorporation of ultra-fast AFM probe technology makes it possible to observe RQT in action, delivering new insight into cellular quality control.