The viscoelastic behavior of soft materials, especially cells and tissues, has been extensively investigated due to its importance in many biological and physiological processes that take place during development and even disease.*

Many techniques are used to quantify the mechanical properties of cells, among them micropipette aspiration, optical stretching, deformability cytometry and atomic force microscopy (AFM).*

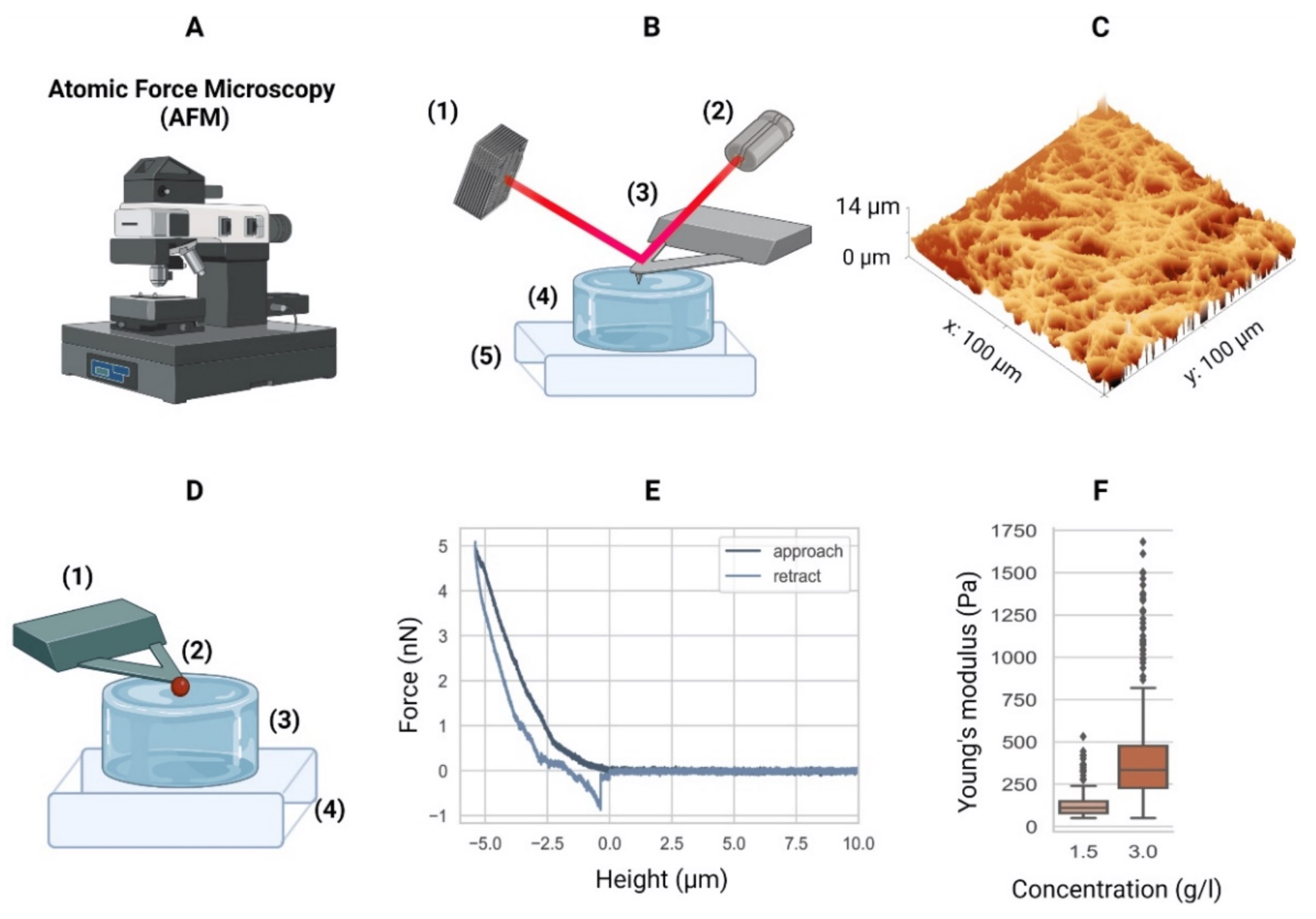

The AFM, in particular, is still nowadays one of the most popular methods due to its conformity with various material types and geometries and the rather simple analysis process of the material properties.*

For a typical AFM indentation measurement, an AFM cantilever, with a distinct AFM tip shape, moves toward the sample with a predefined velocity and indents it until a prescribed force is reached. The AFM cantilever then moves upwards while detaching from the sample. The deflection and displacement signals of the AFM cantilever are processed further to extract the mechanical properties of the sample. Generally, a Hertzian model is fitted to the approach part of the force-indentation curves to quantify the apparent Young’s modulus.*

When applying the Hertzian model, few assumptions need to be considered, such as the material being homogeneous, isotropic, and linearly elastic. *

Cells and tissues, however, show not only elastic but also viscous behavior that is evident from the hysteresis between the approach and retraction segments of the force-indentation curve. Consequently, assessing this viscoelastic behavior is imperative for understanding the complex nature of biological matter.*

A number of studies utilized AFM to measure the viscoelastic properties of cells in both time and frequency domains.*

Ideally, to investigate the whole range of the viscoelastic behavior one needs to probe the material for a long time and observe its response or apply oscillatory signals and evaluate its phase lag. These approaches require the user to alter the probing method and add several steps to account for the time-dependent drift or the effect of the hydrodynamic drag of the surrounding medium. On top of that, in many of studies, the biological materials were probed with a linear approach followed by immediate retraction. The force-indentation curves from these studies were used to evaluate the apparent elastic modulus of the probed material using the standard Hertzian model. However, additional information concerning energy dissipation can still be extracted from the same curves to evaluate the viscoelasticity of the material.*

In the article “An explicit model to extract viscoelastic properties of cells from AFM force-indentation curves”, Shada Abuhattum, Dominic Mokbel, Paul Müller, Despina Soteriou, Jochen Guck and Sebastian Aland propose a new fitting model to extract the viscoelastic properties of soft materials from AFM force-indentation curves. *

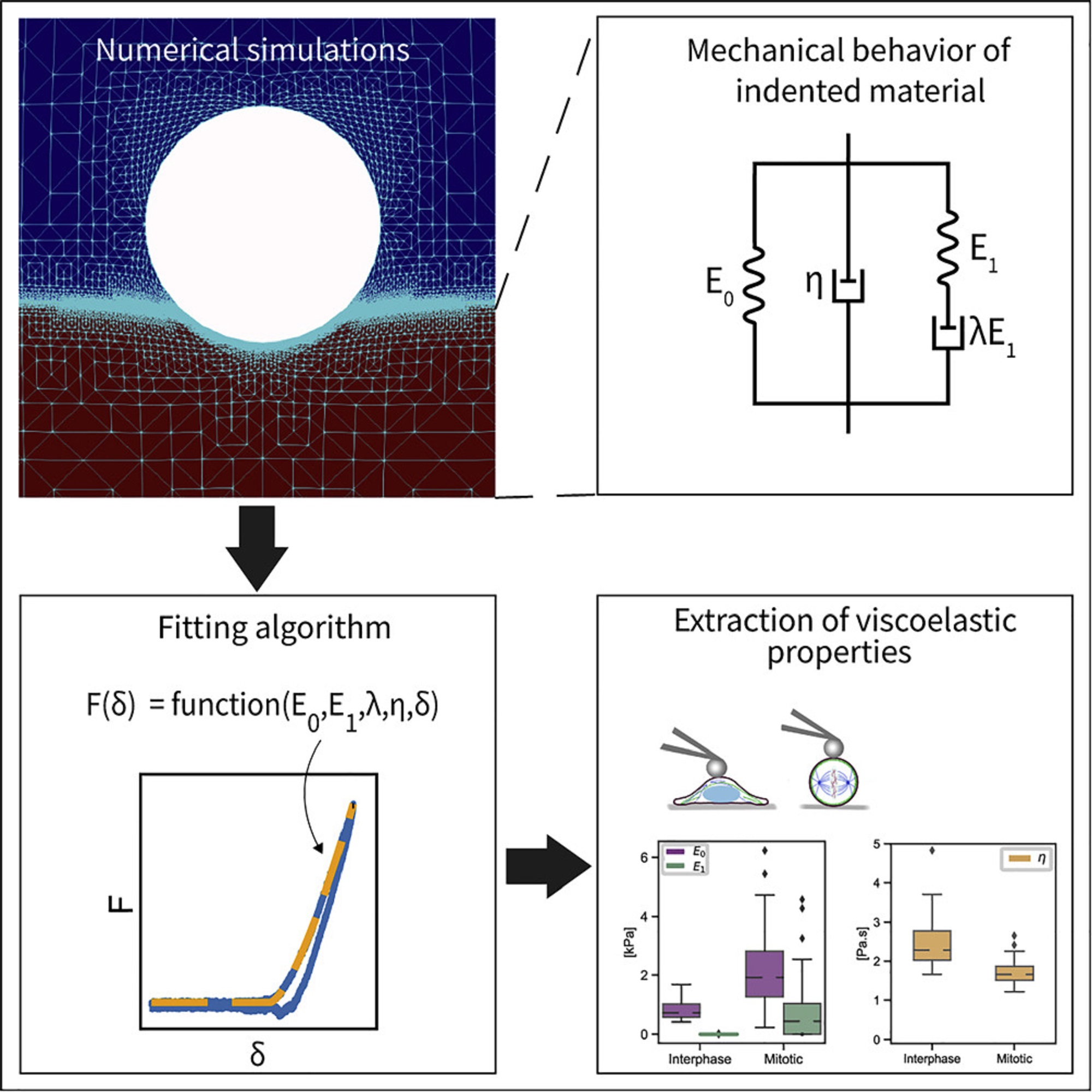

To construct the explicit relation of force and indentation, the authors first use a generalization of Maxwell and Kelvin-Voigt models to describe soft materials, and numerically simulate the indentation of such material with a spherical indenter. *

Shada Abuhattum et al. show that the proposed Kelvin-Voigt-Maxwell (KVM) model adequately captures the force-indentation curves of materials having different mechanical characteristics. *

Based on the simulation results, Shada Abuhattum et al. further propose an explicit force-indentation relation to be fitted to the force-indentation curves. This explicit relation simplifies the association of the mechanical properties with physically meaningful components and processes.

Finally, the authors apply the fitting model to a number of samples, including poroelastic and viscoelastic hydrogels as well as HeLa cells in two different cell cycle phases, interphase and mitotic. *

Shada Abuhattum et al. demonstrate that the distinct nature of the hydrogels, arising from the different crosslinking mechanisms, can be described with the fitting model. For the HeLa cells, the mitotic cells had a higher apparent elasticity and a lower apparent viscosity, implying a stiffer actin cortex and a diluted cytoplasm protein concentration, when compared with interphase cells.*

Their findings demonstrate that the proposed model can reliably extract viscoelastic properties from conventional force-indentation curves. Moreover, the model is able to assess the contribution of the different elastic and viscous elements, and thus allows a direct comparison between the viscoelastic nature of different materials.*

AFM measurements were preformed using a commercially available Atomic Force Microscope. To indent the samples, NanoWorld Pyrex-Nitride tipless AFM cantilevers PNP-TR-TL with a nominal spring constant of 0.08 mN/m were modified by gluing 5 μm diameter polystyrene beads to the underside of the AFM cantilevers using two component glue.*

The AFM cantilevers were calibrated prior to each experiment using the thermal noise method and their accurate spring constant ranged between 0.047-0.059 mN/m. For PAAm and agarose hydrogels, the AFM cantilever was lowered with a constant velocity (5, 10, or 15 μm/s) toward the surface of the sample until a force of 2 nN for agarose and 4 nN for PAAm was reached. These force set points accounted for an indentation in the range of 0.5–1 μm. For HeLa cells, the AFM cantilever was lowered with a constant velocity of 2 μm/s and the cells were indented until a force of 2 nN was reached, which accounted for an indentation depth in the range of 0.5–1.5 μm.*

*Shada Abuhattum, Dominic Mokbel, Paul Müller, Despina Soteriou, Jochen Guck and Sebastian Aland

An explicit model to extract viscoelastic properties of cells from AFM force-indentation curves

iScience, Volume 25, ISSUE 4, 104016, April 15, 2022

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.104016

The article “An explicit model to extract viscoelastic properties of cells from AFM force-indentation curves” by Shada Abuhattum, Dominic Mokbel, Paul Müller, Despina Soteriou, Jochen Guck and Sebastian Aland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third-party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.