Author: NanoWorld

Tunable and parabolic piezoelectricity in hafnia under epitaxal strain

Piezoelectrics are a class of functional materials that have been extensively used for application in modern electro-mechanical and mechatronics technologies. *

The sign of longitudinal piezoelectric coefficients is typically positive but recently a few ferroelectrics, such as ferroelectric polymer poly(vinylidene fluoride) and van der Waals ferroelectric CuInP2S6, were experimentally found to have negative piezoelectricity.

In the article “Tunable and parabolic piezoelectricity in hafnia under epitaxial strain” Hao Cheng, Peijie Jiao, Jian Wang, Mingkai Qing, Yu Deng, Jun-Ming Liu, Laurent Bellaiche, Di Wu and Yurong Yang, using first-principles calculation and measurements, show that the sign of the longitudinal linear piezoelectric coefficient of HfO2 can be tuned from positive to negative via epitaxial strain. *

Nonlinear and even parabolic piezoelectric behaviors are further found at tensile epitaxial strain. *

This parabolic piezoelectric behavior implies that the polarization decreases when increasing the magnitude of either compressive or tensile longitudinal strain, or, equivalently, that the strain increases when increasing the magnitude of electric field being either parallel or antiparallel to the direction of polarization. The unusual piezoelectric effects are from the chemical coordination of the active oxygen atoms. *

These striking piezoelectric features of positive and negative sign, as well as linear and parabolical behaviors, expand the current knowledge in piezoelectricity and broaden the potential of piezoelectric applications towards electro-mechanical and communications technology. *

NanoWorld Pt/Ir coated Pointprobe® EFM AFM probes were used for the sample characterization by switching spectroscopy PFM measurements.

Switching spectroscopy PFM measurements were performed on the bare HZO film surface at room temperature with Nanoworld Pointprobe® EFM in a commercially available atomic force microscope, while the LSMO electrode was grounded.

![Fig. 5 from Hao Cheng et al. (2024) “Tunable and parabolic piezoelectricity in hafnia under epitaxial strain”: [111]-oriented HZO films grown on (110) LAO substrates with different thicknesses of LSMO buffer layers.a XRD θ-2θ patterns of HZO films deposited on (110)-oriented LAO with 20-, 33-, 66-nm-thick LSMO buffer layers. b PFM phase loops of the HZO films deposited on 20-, 33- and 66-nm-thick LSMO buffered LAO substrates. c–e Reciprocal space mappings around the (310) spot of HZO/LSMO/LAO with c 20-, d 33-, and e 66-nm-thick LSMO buffer layers. NanoWorld Pt/Ir coated Pointprobe® EFM AFM probes the sample characterization by switching spectroscopy PFM measurements.](https://www.nanoworld.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Fig-5-from-Hao-Cheng-et-al-2024-Tunable-and-parabolic-piezoelectricity-in-hafnia-under-epitaxial-strain-NanoWorld-EFM-AFM-probe-blog.jpg)

Fig. 5 from Hao Cheng et al. (2024) “Tunable and parabolic piezoelectricity in hafnia under epitaxial strain”: [111]-oriented HZO films grown on (110) LAO substrates with different thicknesses of LSMO buffer layers.

a XRD θ-2θ patterns of HZO films deposited on (110)-oriented LAO with 20-, 33-, 66-nm-thick LSMO buffer layers. b PFM phase loops of the HZO films deposited on 20-, 33- and 66-nm-thick LSMO buffered LAO substrates. c–e Reciprocal space mappings around the (310) spot of HZO/LSMO/LAO with c 20-, d 33-, and e 66-nm-thick LSMO buffer layers.

Tunable and parabolic piezoelectricity in hafnia under epitaxial strain

Nature Communications volume 15, Article number: 394 (2024)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44207-w

Open Access The article “ Tunable and parabolic piezoelectricity in hafnia under epitaxial strain ” by Hao Cheng, Peijie Jiao, Jian Wang, Mingkai Qing, Yu Deng, Jun-Ming Liu, Laurent Bellaiche, Di Wu and Yurong Yang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Ultralow Strain-Induced Emergent Polarization Structures in a Flexible Freestanding BaTiO3 Membrane

Until now, diverse polarization structures and topological domains are obtained in ferroelectric thin films or heterostructures, and the polarization switching and subsequent domain nucleation are found to be more conducive to building energy-efficient and multifunctional polarization structures.*

In the article “Ultralow Strain-Induced Emergent Polarization Structures in a Flexible Freestanding BaTiO3 Membrane” Jie Wang, Zhen Liu, Qixiang Wang, Fang Nie, Yanan Chen, Gang Tian, Hong Fang, Bin He, Jinrui Guo, Limei Zheng, Changjian Li, Weiming Lü and Shishen Yan introduce a continuous and periodic strain in a flexible freestanding BaTiO3 membrane to achieve a zigzag morphology. *

The authors successfully fabricated freestanding BTO membranes with a zigzag morphology using the water-solvation process. *

These films exhibited remarkable curvature-dependent long-range coherence and periodic distributions of polarization. Through experiments and phase-field simulations, Jie Wang et al. observed the presence of H–H and T–T polarization boundaries as well as the formation of large-scale chiral vortex domains. *

Interestingly, these singular polar structures could be induced by ultralow uniaxial and biaxial strains (≈0.5%), which is significantly lower than the previously reported values. The accumulation of charge was found to reduce the formation energy, making the singular polar structures more stable. *

This complicated polarization structure resulting from the morphological variation of the ferroelectric domain provides useful insights into the polarization structure and ferroelectric domain under strain engineering. *

The wrinkled ferroelectric oxides with different strained regions and correlated polarization distributions as well as tunable ferroelectricity can pave the way toward novel flexible electronics. *

Understanding the 3D polarization configuration of a wrinkled BTO membrane is crucial for revealing the relationship between the polarization structure and strain distribution.

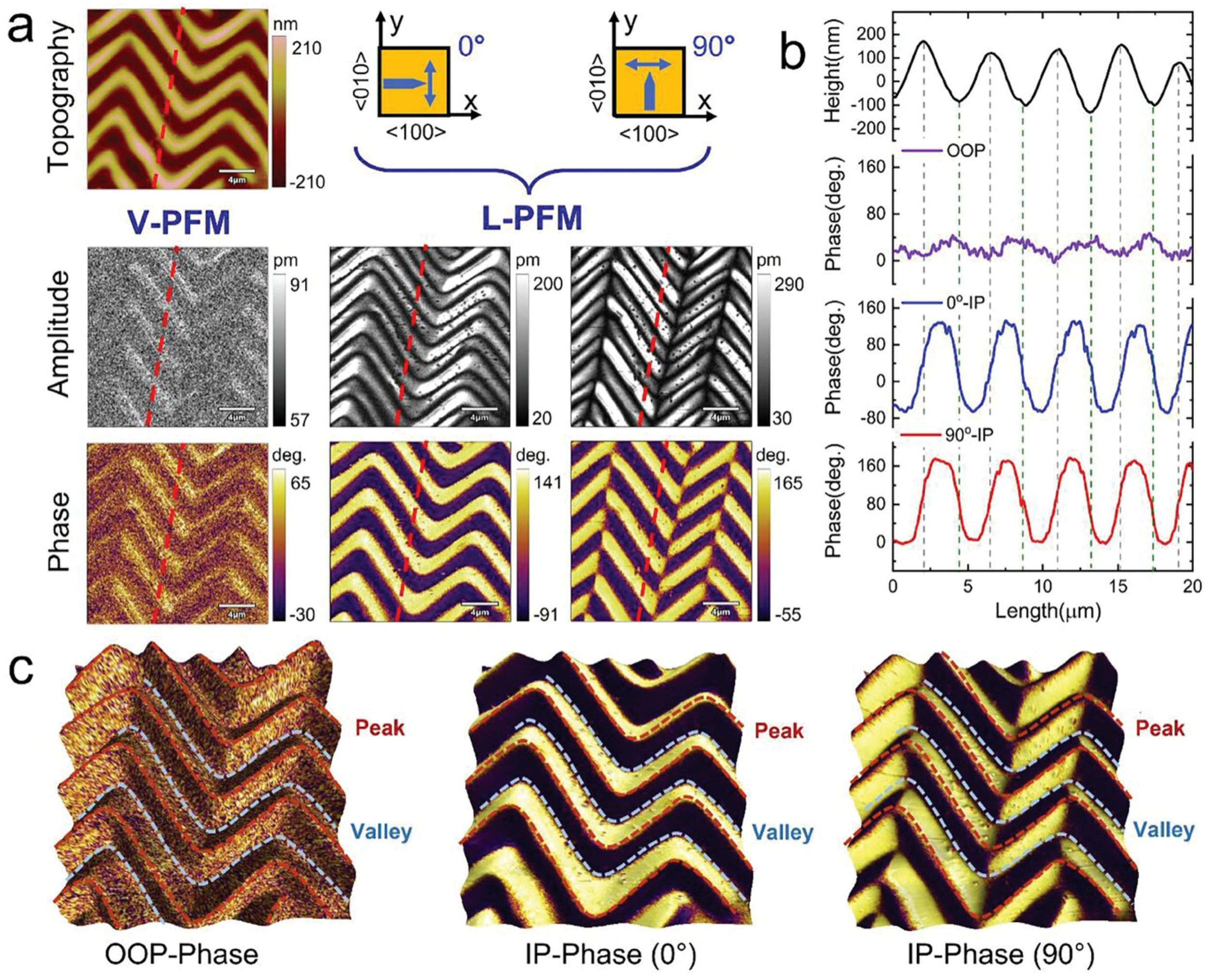

To evaluate the polarization configuration, piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) was employed to obtain the piezoresponse under both vertical and lateral modes (referred to as V-PFM and L-PFM, respectively), and the results are shown in Figure 2a from the article by Jie Wang et al. cited in this blogpost. *

The polarization structures in the freestanding wrinkled BTO membrane were characterized by a commercial scanning probe microscope (SPM).

When the conductive AFM probe (NanoWorld Arrow-EFM) with AC bias was in contact with the sample, the sample underwent regular expansions and contractions due to the inverse piezoelectric effect, which caused the AFM probe to oscillate with the sample.

The oscillation amplitude and phase signals were recorded, which corresponded to the piezoresponse strength and polarization orientation, respectively.

Dual AC resonance tracking PFM (DART-PFM) was used to track the shift in the contact resonance frequency caused by the surface roughness, avoid signal crosstalk, obtain more stable piezoelectric signals with higher sensitivity, and ensure the accuracy of data. The vertical deflection and torsional motion of the probe cantilever were used to detect the deformation of the sample, and the IP and OOP polarization components of the sample were obtained.

To determine the domain structures, both the vertical and lateral PFM images were recorded at different sample rotation angles. The local piezoresponse hysteresis loops were measured by fixing the PFM probe on the selected position and then applying a triangular-square waveform, accompanied with a small AC-driven voltage from the probe.

Electrostatic force microscopy (EFM) and scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy (SKPFM) are widely applied to obtain the surface potential of materials through a dual-channel method.

In the Nap mode, the first-line scanning is used to obtain the surface morphology information of the sample, and then the probe is lifted to a certain height to detect the long-range force (electrostatic force) signal. The operating principle of EFM can be simply interpreted as the phase difference imaging of probe vibration caused by the electrostatic force between the probe and sample. In SKPFM, a DC bias is applied to the conductive tip to balance the surface potential of the sample. The DC bias is equal to the potential difference between the tip and sample, thereby obtaining the relative surface potential distribution of the material. Therefore, EFM qualitatively reflects the potential properties of samples, and SKPFM quantifies the potential of samples.*

Domain structures of zigzag-wrinkled BTO film. a) Topographic image of wrinkled BTO film, giving rise to zigzag pattern. V-PFM and L-PFM amplitude and phase images for two different sample rotation angles of 0° and 90°. b) Line profiles of the height, OOP phase, and IP phase (0° and 90°) data (average over 6 pixels) along the red dotted lines in (a). c) Typical OOP and IP phase images overlapped on 3D morphology. The red and blue dotted curves indicate the position of the peak and valley, respectively.

*Jie Wang, Zhen Liu, Qixiang Wang, Fang Nie, Yanan Chen, Gang Tian, Hong Fang, Bin He, Jinrui Guo, Limei Zheng, Changjian Li, Weiming Lü and Shishen Yan

Ultralow Strain-Induced Emergent Polarization Structures in a Flexible Freestanding BaTiO3 Membrane

Advanced Science, Volume 11, Issue 25, July 3, 2024, 2401657

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202401657

Open Access The article “Ultralow Strain-Induced Emergent Polarization Structures in a Flexible Freestanding BaTiO3 Membrane” by Jie Wang, Zhen Liu, Qixiang Wang, Fang Nie, Yanan Chen, Gang Tian, Hong Fang, Bin He, Jinrui Guo, Limei Zheng, Changjian Li, Weiming Lü and Shishen Yan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.